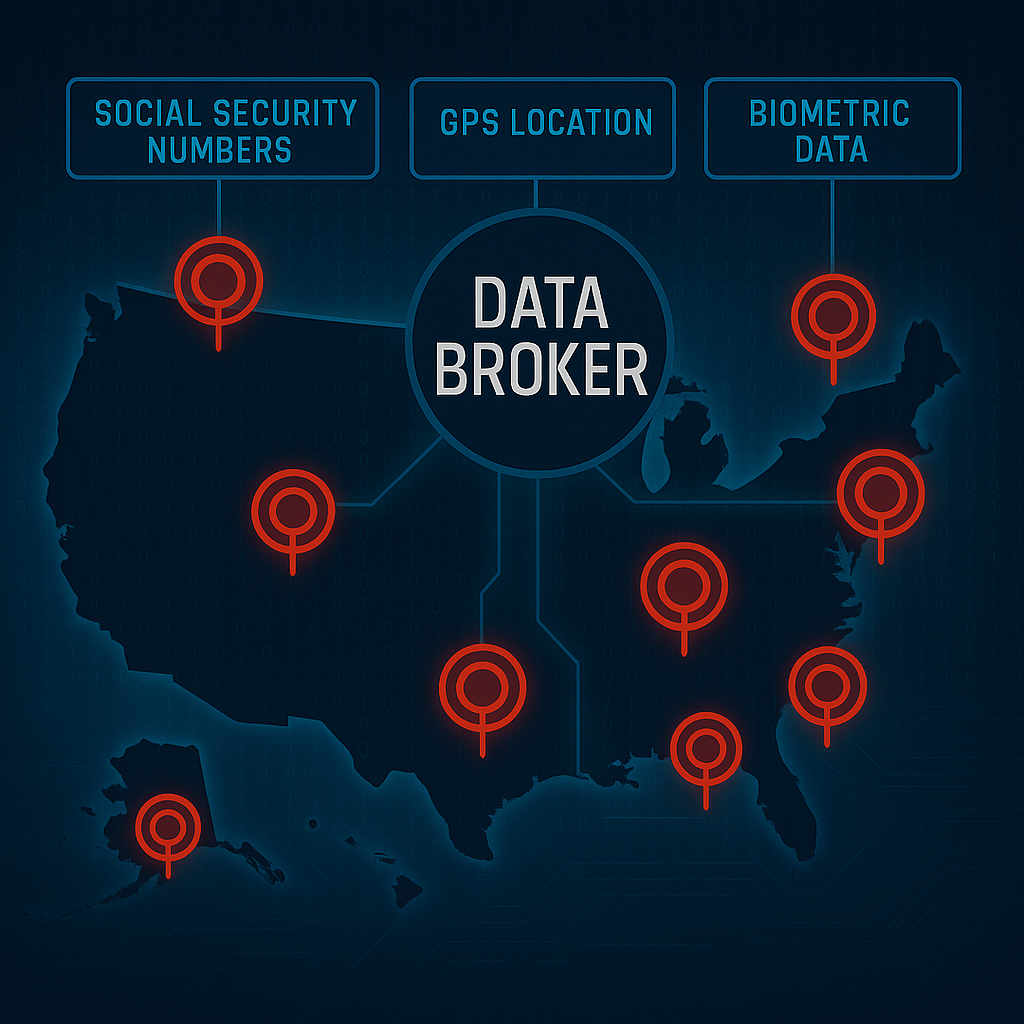

In May 2025, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) quietly revoked what could have been the most significant federal data privacy protection in more than a decade. The agency withdrew the CFPB data broker rule, a proposed regulation that would have classified powerful data brokers, companies that collect and sell detailed personal information without consent, under the legal authority of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). This change would have required companies like Acxiom, Oracle Data Cloud, and LexisNexis to obtain explicit consumer consent before collecting, packaging, and reselling sensitive data such as biometric identifiers, financial histories, geolocation patterns, and court records.

The CFPB, now led by Trump-appointed Director Russ Vought, issued only a one-paragraph notice in the Federal Register declaring that the proposal was “no longer necessary or appropriate,” a major setback for consumer data privacy. While brief on paper, the CFPB data broker ruler reversal carries enormous implications for digital privacy, cybersecurity, and consumer control. Experts from the Atlantic Council, EPIC, and the Brennan Center immediately flagged the reversal as a win for shadowy commercial actors and a loss for ordinary Americans.

This blog breaks down what the CFPB data broker rule was designed to do, why it was reversed, and what its removal means for cybersecurity, national security, and consumer safety. It also explores how states are responding in the absence of federal oversight and what practical steps consumers and policymakers can take now.

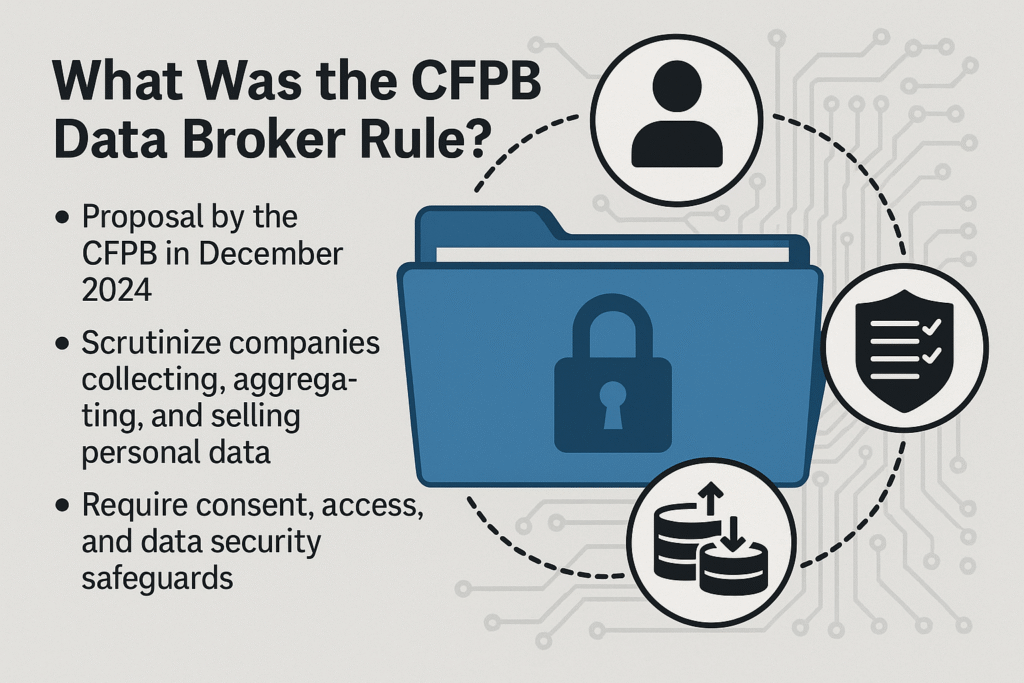

What Was the CFPB Data Broker Rule?

The Rule’s Origin Under the Biden Administration

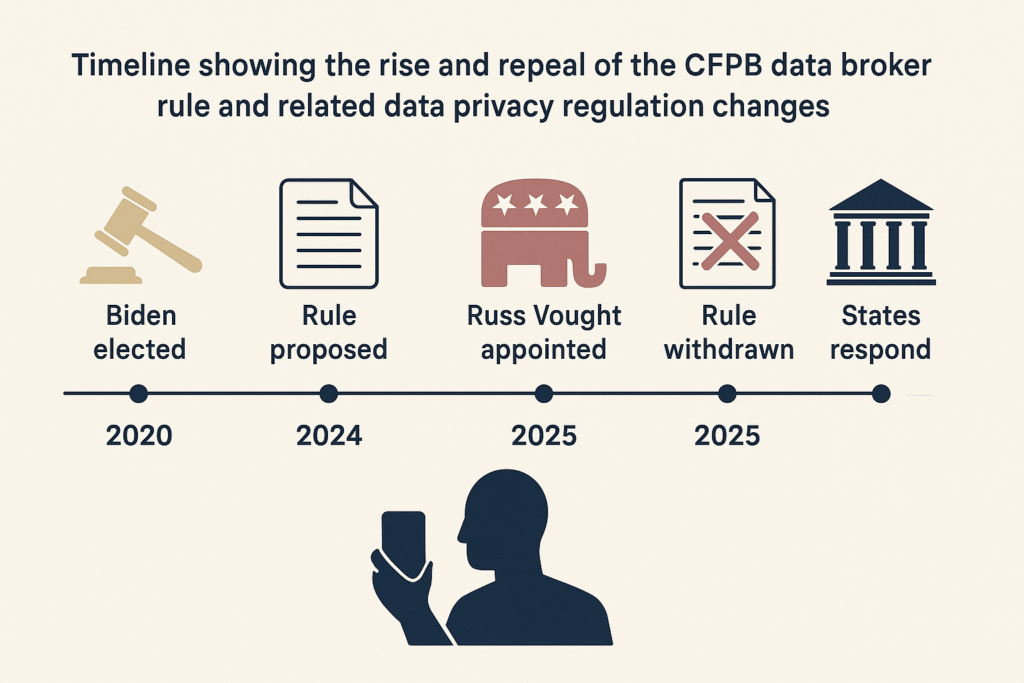

In December 2024, the CFPB proposed a landmark regulation to bring large-scale data brokers under the jurisdiction of the FCRA. These companies had long operated in the shadows, amassing behavioral, demographic, and geolocation data on hundreds of millions of Americans, without the same legal obligations imposed on credit bureaus like Equifax or Experian. The goal of the CFPB data broker rule was to close this Fair Credit Reporting Act loophole and bring brokers into alignment with longstanding consumer protection laws.

The rule acknowledged that modern data practices, such as device fingerprinting, real-time tracking, and AI-generated profiling, have outpaced legacy laws. Classifying major data brokers as consumer reporting agencies would have required them to adhere to the same transparency, accuracy, and consent obligations imposed on credit bureaus.

Scope and Requirements of the Proposed Rule

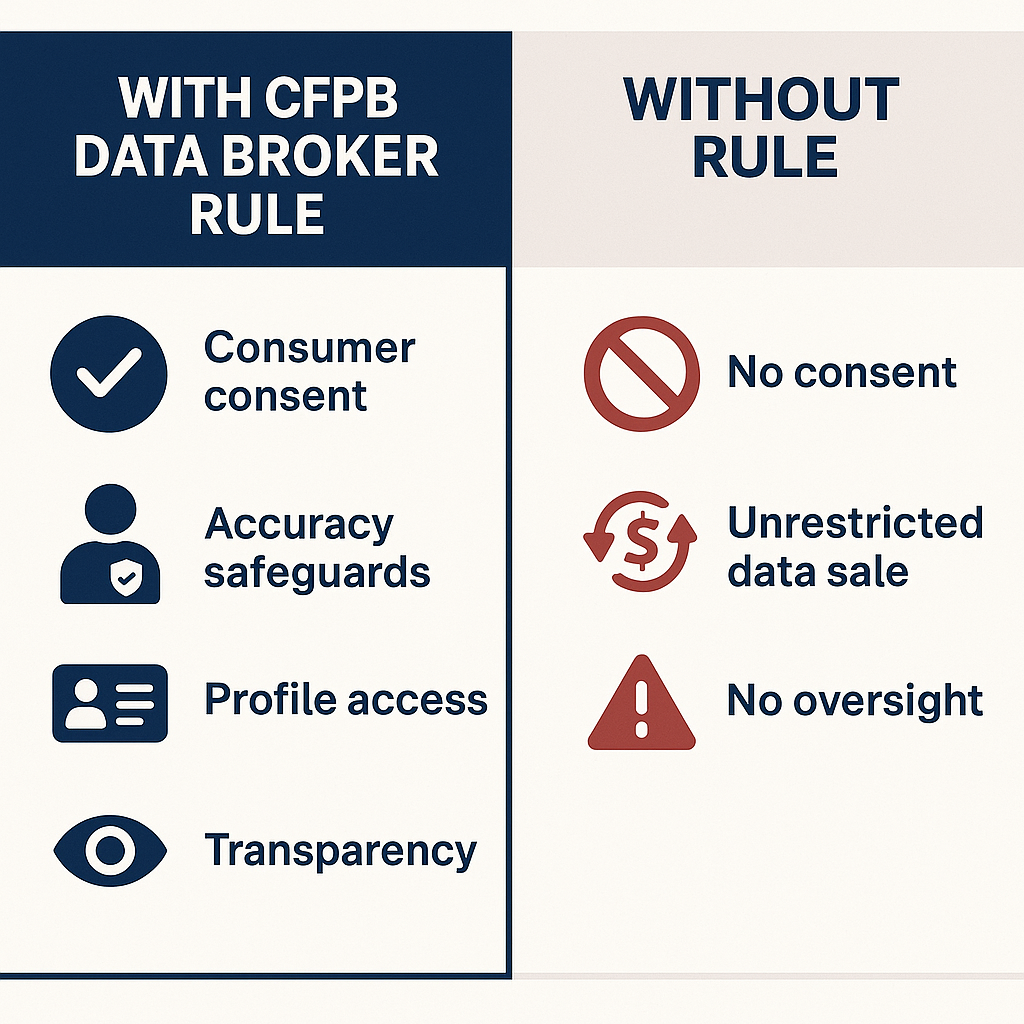

The proposed CFPB data broker rule was sweeping in its scope. It specifically targeted companies that buy, sell, or share personal information tied to individuals’ finances, identities, employment status, and biometrics. If finalized, the rule would have triggered FCRA compliance requirements such as:

- Obtaining explicit consumer consent before collecting or reselling data

- Providing individuals access to their profiles and the ability to correct errors

- Ensuring data accuracy and establishing safeguards for security and disclosure

The CFPB data broker rule would have fundamentally altered the industry’s current model, where consumers often have no idea that brokers exist, let alone how their data is being used.

Goals and Rationale Behind the Rule

The CFPB justified the rule as a necessary update to align federal regulation with real-world digital surveillance practices. According to its notice of proposed rulemaking, data brokers pose “clear and growing threats to consumer privacy, identity integrity, and national security.” Supporters of the rule, including the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and the Brennan Center, emphasized that the data broker ecosystem has become a pipeline for abuse, facilitating everything from targeted ads to political manipulation to state surveillance.

Why the Rule Was Reversed in 2025

Leadership and Policy Shift Under Trump Administration

The reversal of the CFPB data broker rule came quickly after Russ Vought was appointed to lead the agency in early 2025, reflecting a broader shift in Trump data privacy policy towards deregulation. Vought, known for opposing regulatory oversight, moved to dismantle multiple Biden-era consumer protections, including those related to payday lending and student debt transparency. The CFPB data broker rule was rescinded with little explanation beyond a statement that it was inconsistent with the bureau’s current interpretation of the Fair Credit Reporting Act .

This shift was not isolated. It reflected a broader rollback campaign aimed at reducing the federal government’s role in digital privacy and financial regulation. The CFPB’s sudden pivot signaled to industry leaders that oversight of the data economy would be minimal, at least for the remainder of the administration.

Industry Influence and Legal Framing

Lobbying pressure played a critical role. Data brokers and adtech firms had spent months framing the rule as an overreach that would disrupt core industries like advertising, risk modeling, and fraud prevention. By positioning the CFPB proposal as a threat to innovation and small business competitiveness, these companies helped build a narrative that regulation was not only unnecessary but potentially harmful.

Their legal argument was simple. They claimed that classifying data brokers as consumer reporting agencies exceeded the CFPB’s statutory mandate, pointing to a Fair Credit Reporting Act loophole that exempts many data brokers from stringent oversight. This interpretation allowed the bureau to justify walking away from the rule without engaging in a broader public debate.

Silence from CFPB and Rising Backlash

After the rule was withdrawn, the CFPB did not hold hearings, respond to stakeholder concerns, or issue clarifying statements. This silence drew immediate criticism from legal experts and privacy watchdogs. Groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative warned that the rollback would leave Americans more vulnerable to surveillance, profiling, and digital exploitation.

Without the CFPB data broker rule in place, critics argued, the data broker industry is free to continue its operations without transparency, accountability, or meaningful restrictions. The rescission of the CFPB data broker rule was not just a policy shift, it was a signal to the private sector that oversight was no longer a federal priority.

5 Dangerous Implications for Cybersecurity and Privacy

1. Greater Exposure to Identity Theft and Financial Fraud

The CFPB data broker rule would have imposed strict requirements for how companies handle sensitive consumer data. Without it, brokers can continue to collect and sell Social Security numbers, home addresses, employment histories, and other personal details without consent, exacerbating consumer data privacy concerns. These datasets are routinely targeted by hackers, exemplifying the growing data broker cybersecurity risks due to centralized storage of sensitive personal information, including voice-based profiling and impersonation threats as explored here. A breach at Acxiom or CoreLogic, for example, could expose detailed personal profiles of tens of millions of Americans. There is no federal requirement for brokers to notify victims when this happens, leaving individuals unaware of the risks they face.

2. National Security Risks From Unregulated Data Sales

The unregulated sale of geolocation data and behavioral profiles poses a direct threat to national security. A 2024 study by the Atlantic Council found that data brokers routinely sell location data linked to military personnel, government contractors, and federal employees. Foreign intelligence services can easily purchase these data sets through intermediaries or third-party resellers, highlighting significant data broker cybersecurity risks to national security. Without the protections outlined in the CFPB data broker rule, there is no federal mechanism to prevent sensitive data from reaching adversarial governments.

3. Targeting of Vulnerable Communities

Data brokers have a long history of enabling the targeting of vulnerable populations. These include survivors of domestic violence, immigrants, and low-income individuals. When data on housing status, location, or behavioral patterns is sold, it can be used to locate and exploit these individuals. Advocacy groups have warned that such practices enable stalking, harassment, and discriminatory policing. In recent years, data sold by brokers has been linked to immigration enforcement actions and predatory lending schemes.

4. Growth of Shadow Government Surveillance Tools

The CFPB data broker rule could have helped limit how government agencies obtain private data from commercial sources. Its repeal comes at a time when federal departments like the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) have been accused of compiling large-scale surveillance databases using information purchased from brokers. In one 2025 whistleblower complaint, DOGE was reported to have accessed personal data from the National Labor Relations Board and the Department of Education without internal oversight or public disclosure. These types of actions bypass constitutional protections that would otherwise require warrants or formal investigations, raising alarms about the implications of Trump data privacy policy on civil liberties.

5. Collapse of Consumer Consent Norms

The most fundamental consequence of repealing the CFPB data broker rule is the destruction of consumer consent as a governing principle. By declaring that data brokers do not need to follow the same rules as credit bureaus, the government has made it clear that individuals do not control how their information is collected or used. This erodes public trust in digital systems and further entrenches the idea that privacy is optional, not a right, underscoring the urgency for reforms in consumer data privacy.

What States Are Doing Instead

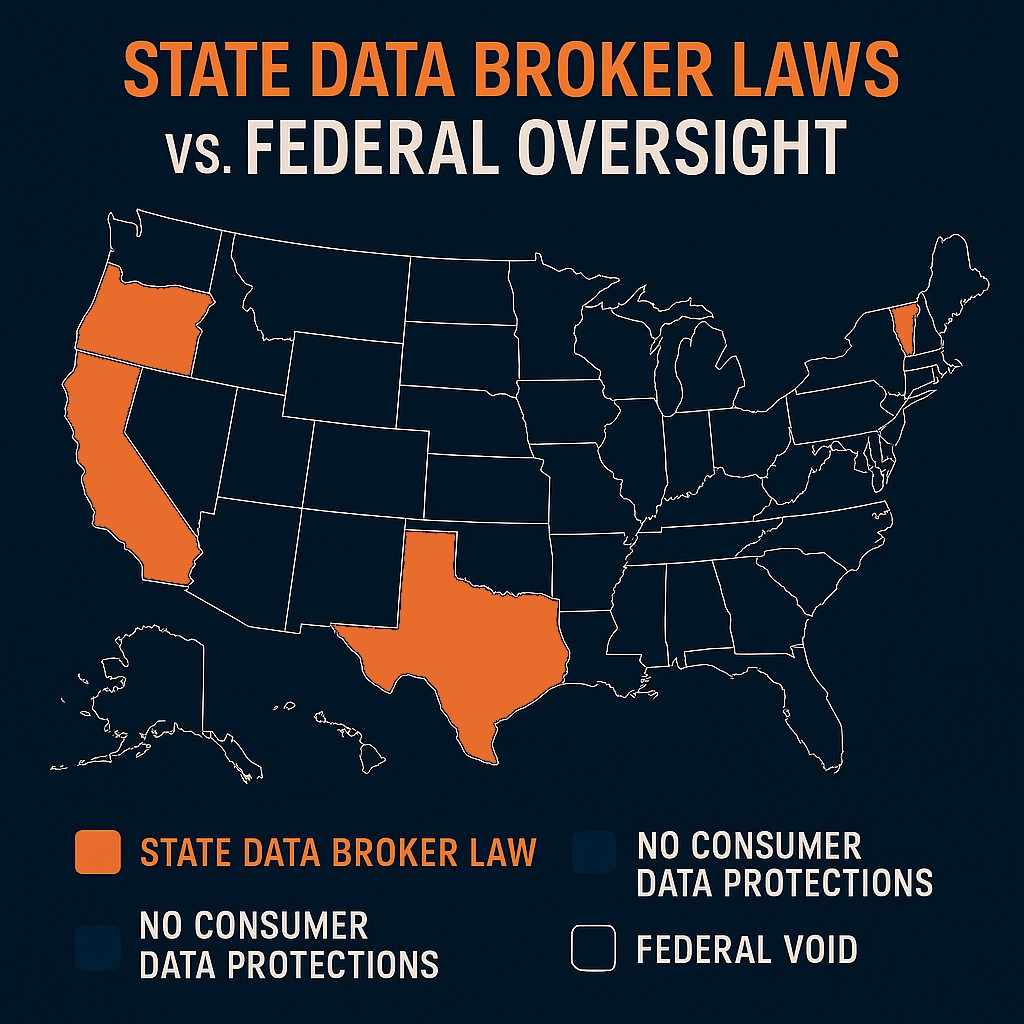

California, Vermont, Oregon, and Texas Respond

In the absence of comprehensive federal regulation, a handful of states have begun taking matters into their own hands. California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) requires data brokers to register with the state and gives residents the right to opt out of data sales. Vermont enacted its own broker registration law in 2018, mandating that companies disclose their data practices and security measures. Oregon followed suit in early 2025, passing legislation that includes enforcement provisions for companies that fail to comply with disclosure and opt-out requirements.

Texas took a more aggressive approach. In January 2025, the state’s attorney general filed a lawsuit against Arity, a data broker owned by Allstate, accusing it of selling real-time driving behavior data to insurance companies without consumer knowledge or consent. This case represented one of the first major enforcement actions against a broker by a Republican-led state.

Enforcement Examples From 2025

The early months of 2025 have already seen signs of stricter enforcement at the state level. In February, California’s privacy enforcement agency fined National Public Data for failing to register as a broker and for failing to comply with transparency rules laid out in the CCPA. Around the same time, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton moved forward with his case against Arity, alleging violations of state consumer protection laws. These cases demonstrate growing willingness among state regulators to rein in data brokers, even in the absence of federal coordination.

Ongoing Gaps and Limitations

Despite this progress, most states still offer little or no protection from data brokers. More than 35 states have no data broker registry, no mandatory opt-out requirements, and no enforcement mechanisms to ensure data accuracy or security. The result is a fragmented legal landscape where your rights depend entirely on your ZIP code, a situation exacerbated by the Fair Credit Reporting Act loophole that allows data brokers to operate with minimal federal oversight.

Even in states with strong laws, enforcement is slow, and consumers are often unaware that these protections exist. Without federal standards, brokers can continue exploiting regulatory loopholes by shifting operations across state lines or partnering with third-party data resellers that operate in weaker jurisdictions. A similar problem exists in other sectors, such as cybersecurity risks in underregulated institutions.

How Consumers Can Protect Themselves in 2025

Opt Out Using Data Broker Removal Tools

While consumers cannot fully stop their data from being collected and sold, they can take steps to reduce their exposure. Tools like DeleteMe, Optery, and Privacy Bee allow users to automate opt-out requests across dozens or even hundreds of data brokers. These services send legal removal notices, track compliance, and offer recurring monitoring. However, effectiveness varies widely. Some brokers refuse to honor opt-out requests, and others re-collect data through third-party sources. Still, these tools offer one of the few actionable ways individuals can push back against unauthorized data collection.

Strengthen Your Privacy Settings

In addition to using opt-out services, consumers should tighten digital privacy settings across all major platforms. Best practices include:

- Turning off location sharing and ad personalization on mobile devices

- Using private or hardened browsers such as Brave, Firefox, or Tor, paired with privacy extensions like uBlock Origin, Privacy Badger, or Cookie AutoDelete

- Switching to privacy-first email and search services such as ProtonMail, Tutanota, or DuckDuckGo

- Reviewing and minimizing app permissions regularly, especially on smartphones and connected home devices

These small steps reduce the amount of trackable information available to brokers and can help prevent downstream misuse. For more strategies, see our guide on AI cybersecurity best practices for consumers.

Monitor for Signs of Abuse or Breach

Consumers should also remain vigilant by monitoring their digital footprint. Free tools like HaveIBeenPwned can alert users when their email addresses or passwords appear in known data breaches. The Federal Trade Commission’s identity theft portal and annualcreditreport.com allow users to access credit reports and flag unauthorized activity. Signs of abuse may include unexpected credit applications, unfamiliar mail or phone calls, or being targeted with hyper-personalized scams. Monitoring your digital footprint also helps detect early indicators of data broker cybersecurity risks that could lead to identity theft or account compromise.

Stay Informed and Get Involved

Understanding the risks posed by data brokers is essential. Consumers should educate themselves about state privacy laws and support organizations like the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), the Brennan Center for Justice, or the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project. These groups advocate for stronger protections, expose industry abuses, and offer tools to help the public stay informed.

To get weekly breakdowns like this and stay informed about real-world cybersecurity threats, subscribe to our newsletter.

The Bigger Picture: Data Brokers, Democracy, and Power

The Political Clout of Data Brokers

The data broker industry does not just influence the private sector. It plays a growing role in shaping political campaigns, lobbying strategies, and policy debates. Behavioral profiles collected by brokers are frequently sold to political action committees (PACs), campaign consultants, and voter targeting platforms. In 2024, at least three data analytics firms that received citations from the Federal Election Commission for improper ad targeting were found to have acquired voter behavior data from commercial data brokers. These activities blur the line between advertising and manipulation, allowing political operatives to craft hyper-targeted messages based on browsing history, credit activity, or even inferred psychological traits, raising significant data broker cybersecurity risks related to electoral integrity.

Surveillance Capitalism Undermines Public Trust

When sensitive personal data becomes a commodity, it does not just affect cybersecurity. It reshapes how people engage with civic institutions. Researchers have documented a chilling effect on free speech and political participation when individuals believe they are being watched or profiled. Whether it is fear of being doxxed, targeted for activism, or tracked across platforms, the commercial surveillance model discourages dissent and weakens democratic accountability. This is especially true for marginalized communities, who are more likely to experience surveillance both by the government and private firms.

Regulation Is Still the Only Real Defense

Technical tools like VPNs, ad blockers, and opt-out services offer partial relief, but they cannot address the structural imbalance between data collectors and everyday consumers. Without federal legislation that establishes clear rules around consent, transparency, and data minimization, individuals will continue to bear the burden of protecting themselves in a system designed to exploit them. The CFPB data broker rule would have created a legal foundation for addressing these imbalances. Its repeal leaves a dangerous void.

Future Outlook: AI, Biometric Profiling, and Political Risk

The dangers of unregulated data collection are accelerating, not diminishing. As artificial intelligence systems ingest data from brokers to train predictive models, the risk of discrimination, surveillance, and coercion increases. Biometric data, including facial recognition, voiceprints, and gait analysis, are being collected without consent and funneled into government and corporate systems. Without urgent action from federal lawmakers, the rollback of the CFPB data broker rule may come to represent a turning point in how privacy is lost not through legislation, but through neglect.

Key Takeaways

- The CFPB data broker rule, proposed in 2024, would have classified data brokers as consumer reporting agencies and required them to obtain explicit consent before collecting or selling personal data.

- In May 2025, the Trump-appointed CFPB leadership revoked the rule, citing statutory interpretation concerns and triggering backlash from cybersecurity and privacy experts.

- Without this rule, data brokers can continue selling sensitive data, including Social Security numbers, biometric details, and geolocation history,with little to no oversight.

- The decision has increased risks related to identity theft, national security threats, and the targeting of vulnerable populations.

- Some states, including California, Vermont, Oregon, and Texas, have passed broker registration and enforcement laws, but protections remain inconsistent nationwide.

- Consumers can reduce exposure by using opt-out tools, enabling privacy settings, and monitoring their digital footprint, but structural reform is still urgently needed.

FAQ

What was the CFPB data broker rule?

It was a proposed regulation to bring major data brokers under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, requiring them to obtain consumer consent and meet transparency and accuracy obligations.

Why was the rule revoked?

The CFPB under Director Russ Vought stated the rule was inconsistent with its current interpretation of the FCRA. The move aligned with broader deregulation efforts initiated by the Trump administration.

Who are the largest data brokers affected?

Major firms include Acxiom, Oracle Data Cloud, LexisNexis, CoreLogic, and Experian, all of which collect and sell data for marketing, risk scoring, and government use.

Can consumers stop their data from being sold?

Not entirely. However, services like DeleteMe and Optery can help remove personal data from broker sites, and consumers can reduce exposure through privacy tools and browser settings.

Is there a federal privacy law protecting consumer data?

No. The United States has no comprehensive federal privacy law. Protection depends on state-level legislation, which varies significantly in strength and enforcement.